Centuries-old movie posters capture a bygone era, and for many silent films that are gone forever, the cards are the only tangible evidence of their existence.

CONCORD, N.H. — “The Gone Millions,” a 1922 silent film with a darkly foreboding title — like the vast majority of films from the era, has all but disappeared into the next century, surviving mostly thanks to lobby cards.

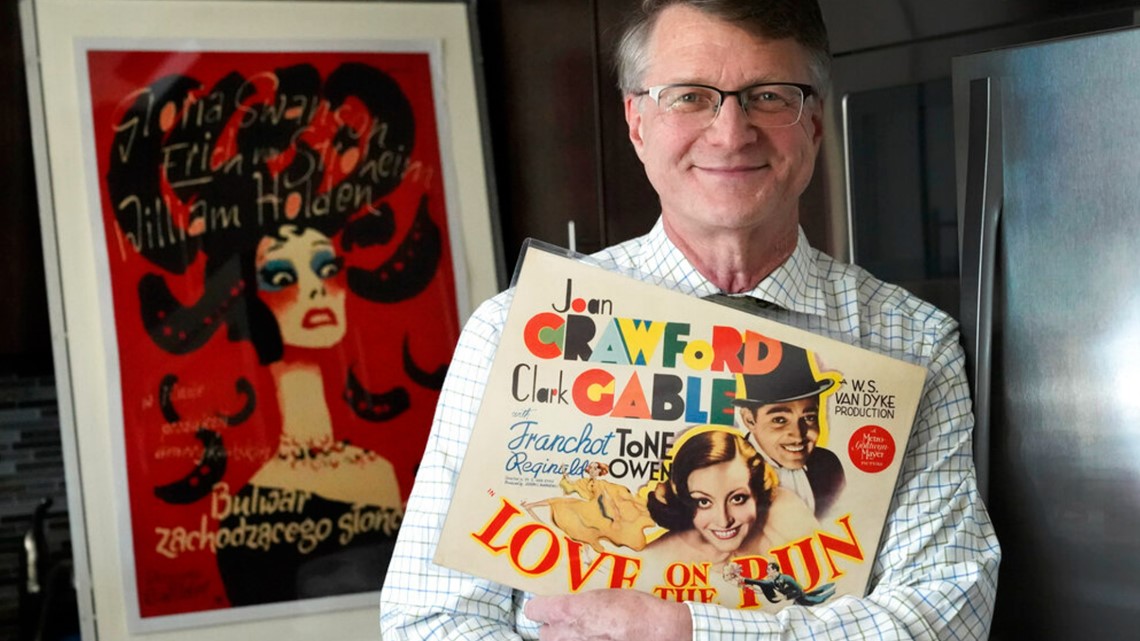

The postcards, barely larger than letter paper, promoted the cinematic novels, comedies and adventures of early Hollywood. More than 10,000 images that once hung in movie theater lobbies are now preserved digitized for preservation and publications thanks to an agreement between Chicago collector Dwight Cleveland and Dartmouth College that began when he bumped into a film professor at an academic conference in New York.

“Ninety percent of all silent films have been lost because they were made on nitrate film, which is fireproof and explosionproof,” Cleveland told the Associated Press. “This means that these lobby cards are the only tangible example that these films ever existed.”

The cards, traditionally 11 by 14 inches (28 by 35 centimeters) and arranged in sets of eight or more, displayed the film’s title, production company, cast, and scenes that might convey the meaning of the plot. Movie screen trailers didn’t become common practice until the rise of the “studio system” era of movies in the 1920s, said Mark Williams, associate professor of film and media studies at Dartmouth and director of the project.

Often displayed on an easel or in a frame and intended for close-up viewing, lobby cards advertised current movies being played as well as nearby attractions.

Today, postcards, many of them more than 100 years old, play an even bigger role, depicting the stars, styles and stories of a bygone era. The legacy of the Paramount Pictures film The Missing Millions, for example, is based on the image of actress Alice Brady and her accomplice, who plan to steal the gold of the financier who sent her father to prison. Brady switched to sound, but that film and a number of others she made in the silent era are lost.

Cleveland, a developer and historic preservationist, became interested in maps when he was a high school student in the 1970s. His art teacher collected some of them, including Lupe Velez and Gary Cooper from the 1929 Western Wolf Song.

“I just fell in love with the color and the deco graphics and those romantic hugs and everything that was incredibly attractive,” he said, “and it just screamed, ‘Take me home!'”

Early lobby cards were produced using a process that produced black-and-white, sepia or brown-toned images, with color added by hand or stencil, according to the report Josie Walters-Johnston, Reference Librarian at the Center for Moving Image Research at the Library of Congress.

By the 1920s, the images had become more like photographs and featured details such as decorative frames and tinting. They were around for decades, and production of lobby cards ceased in the late 1970s or early 1980s, Walters-Johnston writes. But in 2015, this practice was revived when Quentin Tarantino released a special set for his Western “The Big Eight”.

Cleveland delivered boxes from his collection to Dartmouth Media environmental project, where a small group of students is tasked with carefully removing each card from its protective sleeve to be scanned and digitized. Collected by Williams, students also create metadata.

Williams said the project, which began in September and is expected to be completed later this fall, will provide insight into how the films were promoted and what design features went into a given studio’s marketing of the film, among other information that would be hard to come by.

“We will be able to restore access to the really fundamental visual culture of different artists, studios and genres,” he said.

Williams said the project aims to both advance new scholarship and raise awareness of how endangered media history is.

“People, they refer to YouTube, and they think that the history of media is endless and eternal. And both of those statements are false,” Williams said.

When the films, now thought to be lost or left unfinished, were created, the shelf life of the art form was short, Williams said. It was only with time that people began to appreciate cinema as a significant art form and a force of popular culture worth preserving.

The lobby cards confirm the existence of a range of films—from major studios that are still around to smaller ones that have only been around for a few years—and immortalize what Williams described as “a great number of stars—many of whom have been forgotten. »

“There is so much media that is in danger of disintegrating, just turning to dust,” he added, extolling the importance of “historic, vulnerable, ephemeral, extraordinary material” that is at risk of disappearing.

Cleveland also donated 3,500 silent western photo cards featuring stars such as William C. Hart, Jack Hoxie and Buck Jones to the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. He arranged for them to be loaned to Dartmouth for the project.

RELATED: An 80-year-old film finds new life

When completed, the lobby collection will form part of Dartmouth’s Early Film Compendium, which will feature 15 collections of rare and valuable archival and scholarly resources. The compendium, which will be published online by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, will also include more than 7,000 sample frames from early and mostly lost US films, as well as access to more than 2,500 archival films of various genres of early cinema.

The ultimate goal, Williams said, is for “people who are fans, or casual fans, or real scholars, to have access to this material and spark a new interest in it.”

Cleveland – certainly not a casual fan – once owned an archive of 45,000 movie posters from 56 countries. In 2019, he wrote the book Cinema on Paper: The Graphic Genius of Movie Posters. In addition to the Dartmouth project, his collection of lobby cards formed the basis for exhibition in New York focused on women who were prolific filmmakers, writers and producers in the silent film era. He is planning a book on the subject.

“I enjoyed finding, preserving and cataloging these historical documents,” Cleveland said.

When Williams applies computer science, “it just takes him into a whole different realm of the future with the metaverse and everything,” Cleveland said. I feel like I’m being pushed into the future with him, and that’s a very exciting prospect.”

https://www.wtol.com/article/news/nation-world/silent-film-movie-theater-lobby-cards/507-d98cfd11-468a-4a7f-82fd-901572563acb